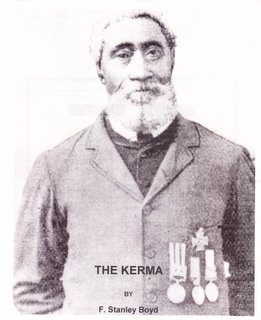

William Hall: A Portrait of a Black Victoria Cross Seaman

This portrait of William Hall, a Black Victoria Cross seaman, was originally published in the Halifax Chronicle Herald’s Central Nova Monthly in June, 1992 at pp. 14 and 15. The article was originally sadly dedicated to my father who died the year before, on November 2, 1991. F. Stanley Boyd has written a draught historical novel of William Hall’s life and times called: The Kerma. The manuscript has not yet been published. This project was assisted by a grant from Convergys Customer Management Inc.

Each September at the end of the summer’s sun and for as many years as I have lived here in Nine Mile River, my thoughts have drifted easily to people and places in the heart.

One such place is Horton Bluff, not far from the hum of my modern computer. And one such person is William (Billy) Nelson Hall, a legend and humble hero who was awarded the Victoria Cross for valor in war in India on November 16, 1857.

A son of Black American slaves, his parents, Jacob and Lucinda, met on the shores of Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay during the War of 1812, and there fell in love. There is nothing more intense as when a love relationship contravenes a country’s law and lovers have to keep it a hidden secret and that they did with brimming excitement until they were able to leave the United States, the home of the brave and the land of the free.

In what was to become known as Nova Scotia, at Summerville, Jacob and Lucinda worked as servants for a Hall family, whose surname they adopted. Eventually, they made their own home in Hants County on the other side of Minas Basin, settling, near the lighthouse, on the Horton Bluff Road. Billy was one of seven children, four girls and three boys.

One warm August day in 1834, Billy, then five, was baptized by a Methodist minister, the Rev. William Temple (1790-1873) at the Methodist Meeting House, near the romantic home of Evangeline and its wishing well of hope at Grand Pre. Records show William Hall was born on April 25, 1829, and was baptized William Nelson Hall on August 28, 1834.

Among those baptized was his childhood sweetheart Lil Dolman, daughter of Margaret and Daniel, also former American slaves.

From an early age Billy loved the sea and sailed between Hantsport and Boston until he was pressed into the American Navy as an able seaman.

When yet a teenager Mr. Hall sailed around the Horn to California as a sailor in the U.S. Navy. The trip took as much as 35 weeks and covered more than 27,000 nautical miles. He sailed on the U.S.S. Savannah frigate under Captain Mervine.

In California, during the Gold Rush of 1850, he reached the low point of his naval career and appears to have narrowly escaped the hangman’s noose.

In the winter of 1852 he renewed his naval career as a bluejacket in Her Majesty’s Royal Navy, a career that spanned 23 years. H.M.S. Rodney was his first British ship. Rodney was a quick roller. He sailed to Crimea and took part in that conflict. He was awarded two medals for distinguished service in that Campaign: the British one with clasps for the battles of Sebastopol and Inkermann and the Turkish government medal. After Crimea, he mustered on the deck of H.M.S. Shannon to sail to the China seas, but as fate would have it he ended up in India.

The India Mutiny

Tuesday, March 17, 1857, Saint Patrick’s Day, was a proper day for the H.M.S. Shannon to set sail for her tour of duty on the China Station. Singapore was her destination to pick up the vice-regal party going on to Hong Kong.

On June 23 the eighth earl of Elgin and Kincardine, a former Governor General of what was to become Canada, James Bruce, moved off from shore on a barge, followed by a flotilla of assorted craft, beneath a heavy salute from the shore batteries. His Excellency’s barge made its way over Singapore’s harbor and slowly passed H.M.S. Spartan and her guns repeated the salute. Over the top was the style of Captain William Peel who organized the grand send off.

Before leaving Singapore Harbor – July 2 brought news of a Sepoy uprising in Indian. The Sepoys, the Native Army of India, rebelled against the British Empire’s expansion, and India’s soil ran red in British blood.

On July 15, the Sepoy army had worn down Sir Hugh Wheeler’s 250 men and some 330 British women and children. Under a flag of truce, Wheeler agreed to surrender given promises of peace from the Sepoy leader, Nana Dhoondopunt of Bithoor. But instead some were killed and others yet alive, along with the dead, were thrown into what became known as the memorial well at Cawnpore. It is said that “one thinks of Cawnpore with a shudder, and leaves it with a sigh.” It is also said that it must be told whenever this sad story is related that the most careful British investigations failed to discover a single case Sepoy mutilation of anyone before death, or torture, or dishonor of women during the India Mutiny.

Cawnpore, about 50 miles from Lucknow, the capital of Oudh kingdom, came under attack and siege by the Sepoys. With time running out for the small garrison at Lucknow facing starvation, low in water and an opposition of some 50,000 Sepoy troops, the crew of H.M.S. Shannon, among other troops, were ordered to quell the uprising. The Shannon sailed for Calcutta and made forced marches overland to Lucknow.

November 16, 1857 was a day of death from beginning to end. Two fortified formidable mosques lay between Hall’s column and the relief of Lucknow, the Secundrabagh and the Shah Najaf. The former fell early that day and the loss of life on both sides was heavy.

The Shah Najaf fell reluctantly at the end of a very long bloody day. The deadly ones on the path forward were the Sepoy archers. With their powerful bows they killed many. A lifeless corpse of smoke and dust settled over the darkening battlefield. It seemed as though only a few seconds of time had passed when darkening crimson shadows of sunset gathered and cast its reach over the death and dismemberment of the day’s proceedings.

Fire red sparks from the enemy’s guns and muskets grew gradually brighter over all sections of the Shah Najaf’s ramparts. Torches were being lit and all the while the Sepoys, former comrades at arms, gestured menacingly for their former British comrades to advance. And advance they did.

The British bombardment, since 4 o’clock that afternoon, had had little effect. So the column’s commander ordered two 24-pounders closer to breach the Shah Najaf’s massive masonry. It was seen as a suicide mission for gunners. When one crew was shot away by the Sepoy snipers and archers another was ordered forward. Hall and Lieutenant Young volunteered. When Young was shot, Hall continued alone to load, set and fire the 24-pounder until the wall was breached. That’s the way it was and Hall was cited for the Victoria Cross. The London Times observed:

“For his valor at the side of a 24-pounder, a black man from Nova Scotia, William Hall, Captain of the Foretop, on H.M.S. Shannon in one of the most supreme moments in all the age-long story of human courage, fired the charge which opened the Shah Najaf walls, and enabled her Majesty’s troops in India to push through to the relief of the garrison at Lucknow. This act ultimately led to quelling the mutiny and the restoration of peace and order in India.”

Hall was presented with the Cross one year and 346 days after the day, November 16, 1857. In fact Hall had forgotten about the Cross until October 28, 1859 on board the H.M.S. Donegal at Queenston Harbor in Cork, southern Ireland, when Rear-Admiral Charles Talbot was piped aboard. All ships and ranks at the station were assembled when Rear Admiral Talbot motioned for the Donegal’s 30-year old leading seaman to come forward to receive the coveted Victoria Cross. Mr. Hall’s chest swelled with pride as the band of H.M.S. Hawke played ‘God Save the Queen.’

Home on Horton Bluff

In 1875, Mr. Hall, 46, retired to Horton Bluff where he lived the remainder of his life with his sisters: Rachel Hall Robinson and Mary Jane Hall. In September 1900 he was interviewed by a Journalist writing an article for The Canadian Magazine that was published in June, 1901. He was quoted as saying:

“It is nothing to have a Cross now; they’re as thick as peas.”

“Do you know,’ the journalist said, ‘that there are thousands of officers in the British Army and Navy who are longing to possess the medal that you have won; many of them, too, holding very high rank.”

He died on August 25, 1904 at age 75.

This year come September, when the swamp grass has grown tall from the summer’s sun and the sun-scorched stalks of cattail brooms chatter in the autumn winds, perhaps my thoughts will be allowed to drift involuntarily to something else, other than this story of Billy Hall, now that it is written. Perhaps the thought of another winter will come to mind, a sobering thought, for you can’t imagine how much I hate to see October go.

F. Stanley Boyd has written a draught historical novel of William Hall’s life and times called: The Kerma. The manuscript has not yet been published. This project was assisted by a grant from Convergys Customer Management Inc.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home